Europe's Indo-Pacific Fancy

BRUSSELS – Australia scrapped a large order of French submarines and went for a project with the United States instead. This confirms a pressing reality for Europe: It is no longer an Indo-Pacific power. It will not become an Indo-Pacific power. And if it keeps overreaching its geopolitical ambitions, Europe might lose its credibility as a “power” all together. If Europe wants to become more geopolitical, it needs to respect geopolitics’ foremost dictum. Geography tells you where to prioritize. For Europe, that’s not in the Indo-Pacific, but its backyard.

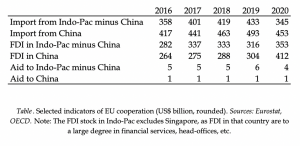

Europe continues to profile itself as an Indo-Pacific power. Countries like France do, but also the European Union, which recently published an Indo-Pacific strategy. That strategy presents Europe essentially as an economic and soft power. But Europe’s economic power is not impressive. Europe, the UK still included, only buys 15 percent of the region’s exports. This is less than the United States and it will soon be overtaken by China. Europe’s development aid to the region is stagnant and its investment mainly in China.

The moral power is limited too. Europe states it can assert rules through advanced trade agreements that also include social and environmental norms. But these norms remain difficult to enforce and advanced trade agreements still cover less than 30 percent of Europe’s trade with the region. It has no such deal with China, for instance. A recent survey among Southeast Asian countries confirms that citizens there appreciate Europe championing the rule of law and climate change action, but question its capacity to display leadership.

The moral power is limited too. Europe states it can assert rules through advanced trade agreements that also include social and environmental norms. But these norms remain difficult to enforce and advanced trade agreements still cover less than 30 percent of Europe’s trade with the region. It has no such deal with China, for instance. A recent survey among Southeast Asian countries confirms that citizens there appreciate Europe championing the rule of law and climate change action, but question its capacity to display leadership.

There also remains a marked gap between the enthusiasm in the discourses of politicians and their willingness to visit the Indo-Pacific. For decades, Asian diplomats have lamented the lack of interest for European heads of state in the region and their reluctance to participate in summit meetings of regional organizations, like ASEAN. If one considers official visits by the French president and the German prime minister, for instance, paid 15 percent of their visits outside Europe to the Indo-Pac, China remaining their most frequent destination.

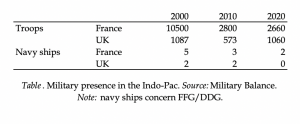

Europe’s military presence is insignificant. France, for instance, the European country with the largest military footprint in the Indo-Pacific has reduced the number of troops in the area from around 10,000 in 2020 to 2,700. These are no expeditionary troops; they merely preserve security in overseas territory like Caledonia and Martinique. It has three small frigates to patrol the exclusive economic zone around those islands. Its intelligence satellites reportedly not even cover the whole area.

The UK has a few hundreds of soldiers in the Indo-Pacific, mostly in a jungle warfare training facility in Brunei. London recently decided to deploy two large patrol ships for a longer period. These two assets are supposed to patrol the entire Indo-Pacific. Chinese news media mocked the deployment of these “less-capable warships”. The deployment of the Queen Elisabeth aircraft carrier to the region remains symbolical. Such presence can just not be sustained.

The UK has a few hundreds of soldiers in the Indo-Pacific, mostly in a jungle warfare training facility in Brunei. London recently decided to deploy two large patrol ships for a longer period. These two assets are supposed to patrol the entire Indo-Pacific. Chinese news media mocked the deployment of these “less-capable warships”. The deployment of the Queen Elisabeth aircraft carrier to the region remains symbolical. Such presence can just not be sustained.

This partially explains why Australia replaced the order for French submarines by an order for American submarines. Besides the fact that the American ones will be far more capable, Australia does not just want submarines; it seeks a life insurance. In the last decade, Europe’s annual defence exports have remained steady around US$ 2.4 billion. Despite an arms embargo, interestingly, annual defence exports to China are still around US$ 260 million. Hence, Europe’s perception as an opportunistic defense mercantilist; not a strong security partner.

Europe remains an ephemeral power in the Indo-Pacific. It is seen as a trusted partner, but also an impotent partner. Some globalists retort that power is inevitably ephemeral these days, that it is about norms and networks, less about warships and big investments; about being a neutral broker, not an arrogant bully. Only about two percent of the respondents in Southeast Asia identify Europe as the region’s most powerful actor, behind China, the US, Japan, ASEAN, and just before South-Korea. Europe’s Indo-Pacific strategy is hence so threadbare that it becomes trivial.

Indo-Pacific activism goes at the expense of more urgent challenges in Europe’s backyard. As the US continues to shift to the Indo-Pacific, the power vacuum in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and Africa causes new instability. That’s where Europe should be. It should concentrate investment, trade, diplomacy, and security capabilities on this area if it does not want to become entirely redundant. Tackling terrorism, piracy, state failure, and regional power politics in this area will likely impress its Indo-Pacific partners more than sending a navy ship through the South China Sea now and then. (Photo: British marine staring at a Royal Navy shipyard in Singapore; Published in EU Observer.)