The emperor remains far behind the mountains

BRUSSELS – About two thousand years ago, a delegation of the Chinese Han emperor travelled to the north of modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan. The embassy wanted to show the two little states, Jibin and Goafu, to show diffidence. A first delegation was killed. Another mission was ambushed. It made the emperor furious, but he deemed a military campaign not feasible. The barracks of the so-called General-Pacifier of the Western Regions were too far away from the restive mountain regions; the palace of the emperor even further.

Now that the Americans exit Afghanistan, the expectation exists that China will absorb the country in its sphere of influence. Indeed, throughout history there were many attempts to enlarge Chinese influence West of the formidable mountain ranges of the Pamir and Tian Shan. Culturally, that worked. The Buddha sculptures of Bamyan, which were molested by the Taliban in 2001, testify of the cultural cross-pollination between China, India, and the Middle East. Afghanistan is a crossroads. Militarily and politically, however, it always remained outside China’s reach.

This will not likely change. Kabul is still about a thousand kilometres away from Kashgar, a small provincial city to Chinese standards. There are no direct hardened roads. The G-314 bends from Kashgar to Pakistan and passes the so-called Wakhan Corridor. Adventurers can cross through this valley into Afghanistan, but it requires a very sturdy all-terrain car and several spare tires to brave the donkey trails. Today, still, Afghanistan remains far behind the mountains. It’s not difficult to block that door, remarked a Chinese professor. And that’s the purpose.

China will continue to try to keep the door closed. Kashgar is a garrison city. From there, soldiers with drones patrol the G-314. The Chinese military also has a few strongholds in Tajikistan, along a narrow road north of the Wakhan valley. From there, the patrol with jeeps and horses through the area. They have one purpose: making sure that the Muslim Uyghur minority in the West of China does not get access to radicals in Afghanistan. The area is very thinly populated, so that remains feasible.

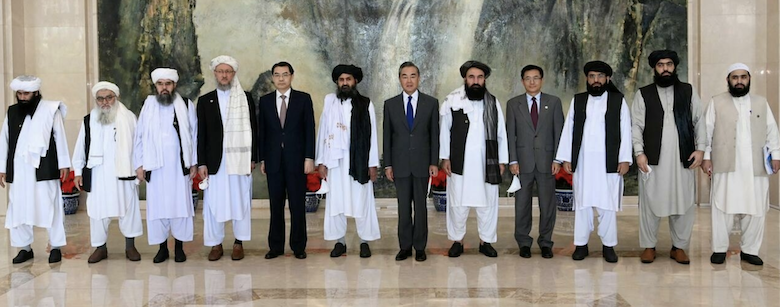

China has long tried to cordon its border off against unrest in Afghanistan. Border patrols were important in that regard, but also discrete talks with Afghan warlords: northern tribes and the Taliban. What China fears the most is a civil war between the Taliban and its adversaries, but also between Taliban factions. And while it will be able to seal the Wakhan corridor, such violence could spill-over in the more densely populated valleys of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. China always distrusted American presence in its backyard; but the future looks even more threatening.

If a civil war breaks out, Beijing will try to contain it. Violence in another neighbouring country, Myanmar, offers some clues about what can happen. In this case, it has sealed of the border, ramped up its intelligence, prompted other countries to cooperate in fighting gangs along the Mekong river and encouraged ASEAN, a regional organization, to mediate. In Afghanistan too, China will most likely lead from behind and push a regional solution instead of going solo and exhaust itself like the US. The Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which also includes Russia and other Central Asian countries, has been founded to fight terrorism. For years, the SCO has practiced so-called peace missions. Now it can put them in practice.

Depending on the success of such mission, China will gradually broaden its economic role in the country. There is no hurry. Iron, copper, lithium and cobalt reserves are attractive but they are found inside China or already mined by Chinese companies elsewhere. For now, they are not worth the risk. It will also take years to unlock Afghanistan. There are some railways in Central-Asia, but they come in different gauges, so that trains have to change wheels when they cross a border. The iron Silk Road still has many gaps. Filling them will cost billions; the returns remaining uncertain. The current limited Chinese export can be channelled via arduous truck drives.

China will not suddenly fill the void that the Americans leave. It will be assertive and proactive, as some experts suggest. Terrorism against China will be punished ruthlessly. It will almost certainly send peacekeepers support to multilateral missions; alongside private security contractors. But it will be cautious and mostly use Afghanistan to strengthen its regional leadership and try not to raise more suspicion among partner countries like Russia about China’s growing power. China intends to lead the regional order, not yet to take over the regional order. For now, the emperor is still far behind the mountains.

Further reading:

Andrew Small on China’s interests in Afghanistan.

François Godement about China’s forward leaning Afghanistan policy.